Disgust factor! The moment your favorite tabloid reports about eye worms.

Certainly not exactly the most appetizing message of the day, but certainly a message with high interaction potential. Let’s take a closer look at what the “oriental eyeworm” Thelazia callipaeda is all about.

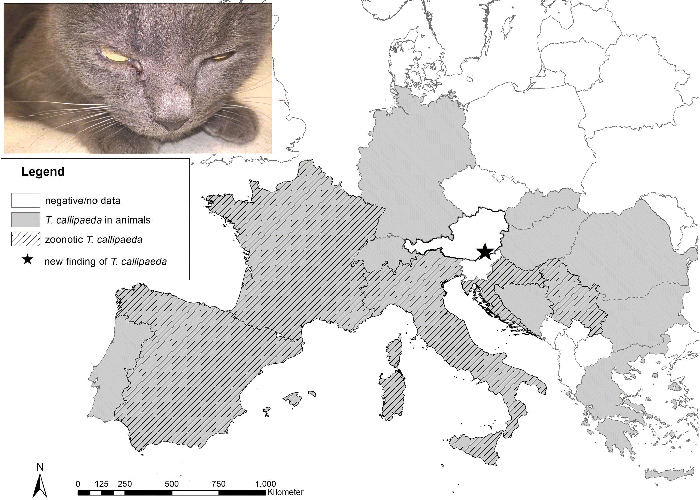

Over the last 30 years, Thelazia callipaeda (Spirurida: Thelaziidae) has been increasingly reported as a causative agent of eye infections in animals and humans throughout Europe. After the cases of canine ocular thelaziosis that recently appeared in Austria, this is the first case of a T. callipaeda infection in an Austrian cat without a stay abroad .

The cat received veterinary treatment, which resulted in complete resolution of clinical signs within 2 weeks.

The results presented in a recent study ( here ) are of great importance to local veterinarians, who were largely unaware of this zoonotic parasite.

Therefore, increased awareness among the medical and veterinary communities is essential to prevent further infections in animals and humans.

About the eye worm

Thelazia callipaeda is a veterinary and medical nematode that inhabits the conjunctival sac and associated eye tissues of domestic and wild carnivores, lagomorphs and humans. This zoonotic parasite is capable of causing a variety of clinical symptoms in the infected hosts, ranging from asymptomatic carriage to mild and severe ocular pathology.

In Europe, T. callipaeda is transmitted by male Phortica variegata drosophiles, which shed infective third-stage larvae while feeding on host ocular secretions. Since the nematode originally appeared in the Far Eastern countries, it was often referred to as the “oriental eyeworm”.

However, since the first European case of canine ocular thelaziosis was described in Italy in 1989 (1989), T. callipaeda has been increasingly reported in animals from France (2007), Switzerland (2008), Germany (2010), Spain (2011), Portugal (2012 ), and discovered in the Balkan region since 2012.

The case in Austria

Back in November 2018, a six-year-old neutered male European Shorthair cat with chronic conjunctivitis of the right eye was referred to his local veterinary clinic in Deutschlandsberg, Austria (see marked star in the image above).

Accordingly, the first signs of eye disease appeared 4-5 weeks before the cat was admitted to the clinic. Ophthalmologic examination revealed unilateral serous ocular discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, and mild conjunctival edema. Additionally, a thread-like, mobile worm was observed under the nictitating membrane of the right eye.

No other ocular abnormalities were noted. The parasite was removed with tweezers, placed in a tube with saline solution and sent to the Institute of Parasitology at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna for morphological and molecular identification. At follow-up 2 weeks after treatment, complete resolution of clinical symptoms was observed and no parasites were detected.

Origin unclear

The current study reports the first case of eyeworm infection in a cat that has never traveled abroad, supporting the existence of local transmission.

, the way in which this parasite was originally introduced to Austria is still unknown . One of the possible explanations is that the eyeworm could have arrived through animal travel, illegal pet trade or import/export of stray dogs, most of which come from infested regions of Eastern Europe. These options have often been cited as efficient ways to transmit and spread zoonotic parasites from infested to non-infested areas.

In this way, three cases of imported infections in dogs from Great Britain that traveled to the countries of Europe where the parasite is very common have recently been described.

In addition, geographical expansion into non-infested areas is also associated with migration of infected wild carnivores, particularly foxes. This is also a plausible scenario that could explain the introduction of the eyeworm in Austria. Therefore, future studies should focus on wild animals to assess their role in the ecoepidemiology of this zoonotic parasite.

Article image by Rattiya Thongdumhyu / Shutterstock.com

Information and passages used in this article (translated) under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) from:

- Hodžić, A., Payer, A. & Shower, GG Parasitol Res (2019) 118: 1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-019-06275-0

- Received January 18, 2019

- Accepted February 20, 2019

- First Online 02 March 2019

- DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-019-06275-0

- Publisher name Springer Berlin Heidelberg

- Print ISSN0932-0113

- Online ISSN1432-1955

Notes:

1) This content reflects the current state of affairs at the time of publication. The reproduction of individual images, screenshots, embeds or video sequences serves to discuss the topic. 2) Individual contributions were created through the use of machine assistance and were carefully checked by the Mimikama editorial team before publication. ( Reason )